Images, notes, and quotes on and around the No Border encampment in Thessaloniki, July 2016 (rendered in the light of anarchist illegalism).

by Ernest Larsen

Continued from Part II

10) Lesson in the Powers of Negativity

There were many signs like the one above around the Aristotle University campus during the encampment.

I have a black tee shirt with white lettering: NO PHOTOS PLEASE. Whenever I saw one of those signs I wished I had brought it with me.

As it has been at all the demos we’ve participated in in Thessaloniki (and elsewhere in Greece), the use of cameras was an issue at all the No Border events and demonstrations.

On trees on pillars on walls and doors this image proscribing the use of cameras. Why? Safety. Self-protection. Self and other protection. The authorities might be able to confiscate such material and use it in criminal prosecutions. Always aware of this taboo against photographic imagery, I often must explain/negotiate/assure people when I pick up my camera. Whatever it takes.

11) A young German friend, who knew something of my political history, introduces me to a young Greek anarchist who has refused mandatory military service and is being heavily fined (to the tune of six thousand euros) for his crime.

From a post on the London Review of Books blog, May 1, 2015: “Twelve Hours a Conscript” by Yiannis Baboulias

If you live in Greece but refuse to serve you can have your passport confiscated. Dimitris Sotiropoulos, the president of the Conscientious Objectors Union, is a 48-year-old graphic designer. He refused to do his two years’ service more than twenty years ago. ‘The heavy sentencing of conscientious objectors that included incarceration stopped in 2004,’ he told me, ‘with the end of the emergency conscription law. But the state has now thought of a new way to crush objectors, by fining them heavily. This turns you from an activist for social change into a debtor. That debt gives the state the right to confiscate assets and even to arrest you.’

For every other offence, you’re put on trial once. For this, they could put us on trial four times a year if the military courts had enough space. They could fine us €6000 every three months.’ There is an unspoken settlement: you can avoid the army, but do it quietly. If you go public, as Lazaros Petromelidis did, you’re in for it: he has been in court 17 times on the same charge.

Dimitris committed his act of insubordination in 1993. (Non-military alternatives for conscientious objectors were introduced in 1997.) For most minor offenses, the statute of limitations would have expired by now. He is three years older than the upper limit for conscription. ‘In 2014, I was found guilty and given a ten-month suspended sentence’ he said. ‘Even if you’re 60, you’ll be put on trial. I’ve filed an appeal, and it’s not over until I clear my name entirely and create a legal precedent.’

Way back on October 21, 1967, I effectively ditched my student deferment when I burned my draft card at the March on the Pentagon, an historically crucial escalation of the anti-war movement from (mere) protest to resistance. This spur of the moment act, a liberating renunciation of privilege, initiated just after twilight, in common with other young men who like me were sitting in on the steps of the Pentagon, commenced a battle with my local draft board in Des Plaines, Illinois. Speedily re-classified as 1A delinquent, I expected along the line to be prosecuted for refusing to be inducted into the army. But I was never summoned to be inducted. What we in The Resistance did not realize was that the Justice Department of the Federal Government had decided on a policy of selective enforcement. The illegalist strategy of The Resistance was predicated on the refusal to be drafted by 10,000 of us. This collective response could very possibly cripple the system. But the strategy was sound only if the government itself followed the law and moved to prosecute all those who resisted the draft. While the collective illegalist strategy of The Resistance did not succeed in practice, on the level of the individual resister it proved decisive: when my draft board sent me a new draft card, reclassifying me as 1A delinquent, I sent it back to Des Plaines with a letter suggesting that the members of the board ought to resign en masse. I kept expecting to be arrested, but I never heard from them again.

In the end, the only serious problem caused by my now permanent lack of a draft card occurred when I tried to get a cabdriver’s license in New York City a few years later. Administered by the Police Department, this bureaucratic process unaccountably (and probably unconstitutionally) required that an applicant submit his draft card to the board of police examiners. I found a friend willing to part with an extra one, erased his typewritten name, and substituted mine. The result was pathetically tattered. Only somebody with seriously impaired eyesight could miss the forgery. I handed the small card to the cop, with no slight expectation of being arrested on the spot. So I’d now compounded the felony I’d committed in burning my card with an additional double felony: defacing an official document piggybacked with the forgery. The cop didn’t notice.

12) Voluntary illegality, whether collective or singular, conceived as a form of direct action, is achieved as a concrete act of solidarity with the excluded.

Depiction of the Durruti Columnm circa 1937. On the reverse side are ration coupons—note the perforations.

Here is how Chris Ealham describes the situation in Barcelona in the years before the Spanish Civil War:

The direct action protest culture of the anarcho-syndicalists fitted within the traditions of popular protest in a city in which street fighting with the police and barricade construction were all inscribed in the history of urban protest from the nineteenth century. Part of the CNT’s appeal stemmed from its readiness to erect a militant organisation around these rich and rebellious working-class cultural traditions. In this way, CNT tactics like boycotts, demonstrations and strikes built on neighbourhood sociability: union assemblies mirrored working-class street culture, and the reciprocal solidarity of the barris was concretised and given organisational expression by the support afforded to confederated unions. Equally, the independent spirit of the barris was reflected in revolutionary syndicalism and its rejection of any integration within bourgeois or state political structures. On the other hand, the exclusionary tendencies of the barris, such as the sanctions of ostracism imposed on those who defied communal values, were now extended to ‘scabs’. In this way, the independent traditions of the barris helped to define the modus operandi of the CNT, and although the rise of union organisation brought with it a more ‘modern’ and disciplined culture of protest, the anarcho-syndicalists developed a broad ‘repertoire of collective action’, which accommodated many of the ‘self-help’ strategies that had evolved in the barris. Firm believers in the spontaneous self-expression of the masses, and in strict opposition to the socialists, who maintained a sharp distinction between the revolutionary and the ‘criminal’, the libertarians emphasised the inalienable right of the poor and the needy to secure their existence, ‘the right to life’, by whatever means they saw fit, whether legal or illegal. They also encouraged popular illegality, such as eating without paying in restaurants, an activity that became very popular with the unemployed and strikers. At the same time, the CNT sought to refine popular urban protests: whereas the largely spontaneous street mobilisations brought temporary control of the streets, the CNT desired a more permanent control of the public sphere and a revolutionary transformation of space.

13) From an article by Spiros Sideris, Athens, May 11, 2016, Independent Balkan News Agency:

Four more refugee hosting areas are to be created in the region of Thessaloniki. As stated to the representative of the Coordinating Body for Refugees, Giorgos Kyritsis, “we proceed to hire four more industrial-commercial spaces in Thessaloniki’s wider area for hosting refugees”.

Meanwhile, referring to the four areas in Thessaloniki, which came up during the process of finding industrial and commercial facilities for hosting refugees, he commented that the place in Oreokastro is operational, while one more is being prepared in Kalohori and preparations will soon be completed for the last two, in the same vicinity. The transfer of refugees to Vagiochori is expected very soon. It should be noted that in the wider region of Thessaloniki function refugee reception centers in Diavata, at the port of the city, Oreokastro and Lagkadikia. As regards the process of decongesting Idomeni, the representative of the Coordinating Body for Refugee believes that in the last 15 days at least two thousand people were transferred from Idomeni to accommodation centers.

v. de·con·gest·ed , de·con·gest·ing , de·con·gests. To relieve congestion, such as of the sinuses.

hosting

reception

Once again, learning the new meanings of old words.

Inflatable (tryptich/Sherry Millner)

14) Is it true or merely a truism that every law functions as a border? Break through—or even make the attempt—get caught, and you will be punished, you will suffer. Thus the slogan/demand/imperative No Borders might also be taken to imply a radical reworking of legality, ultimately touching on the perspective of the other abolitionist social movements gaining strength, such as the anti-prison movement, mentioned earlier. In both cases the partially occluded but essential point of attack is the validity of the wall itself.

Outside Xanthi Detention Camp, February 2015

While we were in Greece in June 2015 we were briefly—for a mere week—illegal. Unintentionally. Thanks to the deliberate misdirection of the Aliens Bureau in Thessaloniki (a subsection of the Police Dept.) we were prevented from getting an extension of the 180-day Schengen agreement rule. At once amused and angered I requested an audience with his Honor, the Chief of Police, for a review of our situated illegal status. Sadly, I was refused. Having now broken the Schengen agreement law, we were each subject to a heavy fine and perhaps banned from further European travel for as much as two years. However, at the crucial moment when we could have been apprehended, as we were attempting to leave the country en route to Turkey (not a party to the dreaded Schengen) I diverted the friendly customs officer by presenting our little black dog to his attention. This meager stratagem worked and off we were, scot-free, Schengen-free.

So the refugees are in point of fact welcome in Thessaloniki, to some substantial portion of its citizens, who are eager to help out. But the authorities (the pseudo-left Syriza) cannot permit this perspective to remain visible and functioning. It gives the lie to the hospitality centers, it pulls the rug out from under them. So they resort to the governmental exercise of force against the refugees they are pledged to protect and against their own citizens.

Two days after the No Border events had finished, “a grand scale police operation targeted the social movement and specifically the structures of migrants’ self-organization.” Three occupied migrants’ homes with dozens of inhabitants were evicted and evacuated—one of them, Orfanotrofio, immediately bulldozed to the ground, destroying tons of medical and relief supplies and all the belongings of the migrants and their anarchist allies in the building, a former orphanage, that had been empty for five years and was owned by the Greek Orthodox Church.

“It was made perfectly clear that practical solidarity and communities of struggle where locals and migrants fight together are most threatening for the authorities and the dominant order.” Of course, there were many arrests and the trials continue, as does the effort to create new spaces, new landscapes. If three are destroyed then four new ones will be established.

Refugees protest in central Athens at evictions of squats in Thessaloniki, August 2016. Orestis Panagiotou/EPA.

Dimitris Dalakoglu/Antonios Alexandridis:

In a series of raids on July 27, the Greek police arrested and moved on dozens of migrants and refugees living in squats in the city of Thessaloniki. The clampdown on these squats, which were run by refugees, volunteers and anti-authoritarian groups, is an example of how refugees are being criminalised at the hands of the authorities across Europe.

Some of these migrants and refugees had come from the largest makeshift refugee camp Europe has seen since the end of World War II. The camp, based at Idomeni on the Greek-Macedonian border, was evacuated in May 2016 by Greek police. Thousands of Syrians, Afghans and other refugees of different origins resisted their displacement from Idomeni. They knew that by staying on the border they were highlighting the real international scale of the migration crisis gripping Europe.

The next chapter of this refugee drama moved into Greece’s cities. Upon the closure of the camp at Idomeni, the Greek government, in co-ordination with the EU, UNHCR and international NGOs, began to move people into smaller camps around the country. The majority are situated on the peripheries of Athens and Thessaloniki. There, contrary to the promises made by the authorities during the relocation in May 2016, neither are the conditions better nor is the pre-registration for the EU’s asylum relocation programme taking place.

… the summer heat in many of these urban camps makes life unbearable. Often the food is insufficient and food markets are too far away. Daily outbreaks of violence among different groups that fight either in competition for the scarce resources or due to their frustration for the uncertainty they experience makes life in these camps dangerous. At the same time, entry for everyone apart from the staff working in camps such as the one at Idomeni is usually prevented by the police and the military who are guarding the periphery. Now activists and volunteers who have spent the last year carrying out all the tasks necessary for the welfare of refugee populations face increasing difficulties in gaining access to the camps unless they are certified by an approved international NGO.

Squats Offer Hope

Since September 2015 refugees and migrants began to be offered an alternative to the camps: a refugee shelter squat was set up on 26 Notara Street in Athens. This was organised by groups of refugees together with the organisations No Borders and Refugees Welcome and other anti-authoritarian and left-wing movements. These have been very active in the effort to tackle this humanitarian crisis.

The idea behind the squat was not just to provide shelter but also to provide tools for the refugees to help manage their own lives. The overarching aim was to help the residents regain their humanity by escaping social marginalisation and creating new social bonds. By actively participating in decision-making and everyday tasks regarding the place where they live, migrants and refugees developed avenues to take part in the social and political life of the city. Due to the success of this project, other Greek and international groups followed this strategy and over the last year from Thessaloniki to Amsterdam unused buildings have been appropriated as refugee settlements.

But on July 27, three of these self-organised refugee shelter squats in Thessaloniki were evicted in a mass police operation that aimed to shutdown unofficial shelters for refugees. One of the buildings, a former orphanage, belongs to the Church of Greece. Although the building was abandoned for decades, a few days after its occupation by refugees and activists in December 2015, the local Orthodox Church of Thessaloniki claimed it wanted to demolish it to build a hospice. The evacuation triggered protests against the archbishop of the city who has made xenophobic statements several times in the past. In the raids, 74 people living in the squats were arrested. The “criminalised” migrants from countries including Morocco, Algeria and Pakistan living in the squats were sent to detention centres. The “legitimate” refugees—for example those from Syria and Iraq—were sent back to their predesignated camps.

On the one hand, the European and Greek authorities are not effectively helping migrants and refugees. On the other hand, they are cracking down on any alternative self-organised initiatives by refugees and members of the public. So how will the refugees’ welfare be organised?

Only two days after the evictions, it was reported in some Greek media that millionaire and Lionsgate Films founder Frank Giustra intends to open a refugee housing facility in Greece. This news, together with similar philanthropic initiatives, has received plenty of positive publicity and was welcomed by the authorities. It shows how the migrant and refugee crisis gripping Greece is gradually being used to advance a privatisation of welfare, which is being outsourced to philanthropic institutes and other non-state professionals of aid. Volunteers, activists and self-organised refugees are paradoxically excluded. It looks like this attack against the refugee squats is just part of an effort to create a controllable, gentrified international aid environment. Within this context, the humanitarian aid industry can operate without interruptions from those who expect nothing more in return for their help than friendship and human solidarity.

The Case Poclain 170c visible here is not a bulldozer but a hydraulic excavator. CNH Global now owns Case which some years ago gobbled up Poclain. Poclain was started in France by a man named Georges Bataille. The Georges Bataille I am more familiar with was you might say an excavator of sorts.

15) Aug 27, Thessaloniki. I had to see what was left of Orfanotrofreio. At first it seemed inaccessible, closed to view, but for a hole in the makeshift tin gate, securely locked up. Soon I decided to climb over two 10-foot-high walls (stone surmounted by iron fencing painted forest-green), skirting a strip of razor wire, to get inside the ruins of Orfanotrofeio in order to video the remains. The weapon the police employed to destroy the squat occupied by the migrant families and their anarchist supporters was a Case Poclain 170c hydraulic excavator. This monster had done its work well.

What remains of Orfanotrofeio

The old orphanage building, gifted five years earlier to the Orthodox Church by the previous conservative government but left unused until squatted, was leveled to its foundations, as if it had been repeatedly bombed. Heaps of rubble, broken and crumbled brick, tangles of wire and bent steel rods, on the perimeter a few elements intact enough to be recognizable as what once might have been a kitchen, a stretch of wall painted bright red, another wall covered with nearly intact political posters, frayed edges flapping in the slight breeze, some gutted exterior space that might have been used for hanging laundry, for children to play, for sharing a drink, or a smoke, look at the stars.

Slowly, I walked through searching for bits of the visible remains of the dozens of refugees and migrants who’d been seized by the police without warning very early on the morning of July 27, leaving behind all their belongings, as well as tons of foodstuffs, medical supplies, clothing gathered for distribution over the course of months.

I found single shoes—a man’s white sneaker, a woman’s low heel blue leather—lots of clothing half-buried, a sweater, a shirt, curled up in distended shapes. A children’s book: the Greek title: “How Animals and Plants Live.” Children’s colorful plastic toys slathered in dust. In the middle of a sandbox, a small pale-blue pail filled with sand and carefully leveled off, as if the child would soon be back to continue her game. Several yards off, the head of a teddy bear stuck up through some broken slats and a maze of stiff wiring, as if courageously but piteously awaiting the rescue of what we now must call first-responders. On a markerboard these mind-boggling words are scrawled in English: “We love to play.”

I had my video to do, to think about. I didn’t have the time to be horrified. Some guard might show up at any moment to toss me out. But: it was horrifying. No one was killed or even seriously injured in this police invasion, this wholesale destruction without warning or rationale of ordinary people’s fully and no doubt lovingly improvised home and possessions, people who’d already been forced to leave behind their homes and possessions, except for what they could carry. This time they weren’t allowed to gather anything. Here and there and really everywhere, as I’ve tried to indicate, some of the physical elements, fragments, of their daily lives were just visible enough amid the rubble to feel like all the evidence that could possible be needed to convict that old institutional trio of conspirators of an extraordinarily perverse and wholly gratuitous act of wanton destruction. I speak of the police, the Syriza government, and the Greek Orthodox church. In every nation-state on the planet this triumphant trinity gangs up as the great enforcers of law and order. This three-part symphony of barbarism: cops, state, church.

At the trials a woman prosecutor asked a witness—and after all, no matter what, you did know that squatting was illegal did you not?

Yes, of course and didn’t you know that until very recently it was illegal for there to be woman prosecutors and women judges? How did you think that changed? Through respect for the law?

None of the migrants of the three evicted buildings was charged. Why? Because the anarchists had made sure that they all had some sort of legal status.

L. wrote:

1) Orfanotrofio will now be remembered as a successful experiment of migrants’ self-organization that won the war against the mafias, since the eviction did not give us time to collapse under internal pressure…

2) Migrants’ self-organized structures, which the government had to tolerate for a while as part of its “humanitarian volunteer” public profile, that it used to ask for EU money; and

3) How 1 and 2 fit in with the biopolitics of fortress Europe, which in this country can be broken down to three quasi-strategies:

a) “don’t make places too comfortable, even though there is money to fix them,”

b) “try to exploit your status as a transit country by nationally investing in the black economy of trafficking” and

c) “hand over detention centers and settlements to NGOs and all kinds of agents (besides dealers and traffickers) and allow them to become the testing ground for population management.”

16) In an interview, Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (a Bolivian historian/activist) says: “When you have the logic of inclusion, you have enormous possibilities of intercultural action.”

What I have been calling here a politics of the excluded, with a blink and a nod, obviously (from the other side of the wall, that is) becomes a logic of inclusion.

Cusianqui says: “When you have unity, you are without possibilities. It is closed. The possibility of change is because there is contradiction. If you leave it open, there are possibilities—that the margins become the center, that the one side turns to the other side. There is fluidity, there is movement. If you reach the ‘synthesis,’ you reach the Communist state—another fucking state!”

The field of experimental culture, conceived as a laboratory for imagination of potentialities, whether realizable and/or not. Maybe. Generally speaking, the risks of improbable possibilities are first encountered in the borderless terrain of the imagination.

From Eric Hazan’s History of the Barricade:

It is no accident that the most famous painting of an episode in the history of France—Liberty Guiding the People—was made by Delacroix after the Three Glorious Days (of 1830). This painting shows what it is that permits us to speak of an apogee: in the heat of the action, alongside Liberty we see amid the smoke a worker, a student and a youngster, three types who fought side by side, as all witnesses concur.

Liberty Guiding the People, 1830

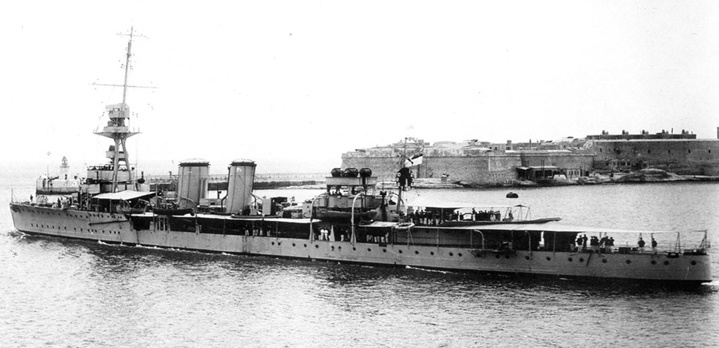

17) Let us remember that the reigning monarch of England has been married since 1947 to a Greek prince: Philip/pos, who was baptized in the Greek Orthodox Church and whose uncle Constantine I was the last and final king of Greece. Following Constantine’s forced abdication and banishment in 1922, the British naval vessel HMS Calypso was dispatched to evacuate Philippos’s father Prince Andrew and his family from Greece. The infant Philippos was carried to safety in a fruit box. In other words, he’s a royal migrant, currently living very safely in the massive fruit box known as Buckminster Palace.

HMS Calypso

In September the British and French announce plans to construct a “Great Wall of Calais” to keep migrants from the port. “This measure is intended to further protect the Rocade from migrant attempts to disrupt, delay and even attack vehicles approaching the port,” the British Home Office said in an emailed statement. The Rocade is an access road leading into the port.

Calypso.

Daylight comes and I want to go home.

I hear his majesty Harry Belafonte sing the lyric.

Daaaaaay-o.

I am trying to remember if in any of his film roles Harry Belafonte, a lifelong activist, played a revolutionary.

As I finish this piece, the Jungle at Calais is being forcibly evacuated by the authorities.

Postscript:

A most trusted comrade writes to me from Thessaloniki, generously offering some last-minute corrections and this political remark: “The No Border movement, the same as the libertarian movement at its best, is neither legalist nor illegalist, it cares for global justice without taking into consideration legal or illegal issues, except for reasons of practicability and effectiveness. In my opinion, ‘illegalism’ is a trap (‘legalism’ too, but this is obvious).”

To this compelling image of the trap I can only add that, according to the working hypothesis of these notes, the aporia legalism/illegalism, with its impregnable either/or border between the two interdependent positions signified/punctuated by the slash ( the mark / ), is also a trap. Unlike a barbed or razor wire fence it is impossible to scale, break through, or crawl under.

Heads I win. Tails you lose.

Heads you win. Tails I lose.

Okay, but which should you choose—heads or tails?